Despite what we are asked to believe, pharmaceutical marketers used to have it easy. Marketing predominantly to doctors, companies positioned their patent protected drug against competitive products, seeking any meaningful differentiation to drive market share (or occasionally market growth). “Price” was exogenous to the marketing mix; constantly increasing in the US, constantly declining in most of the rest of the world. However, soaring healthcare costs have resulted in governments, health services and payers taking an active role to curb this unsustainable trend. These new customers have significant power and in past years have redefined the value of pharmaceutical products. What’s out: innovation. What’s in: outcomes.

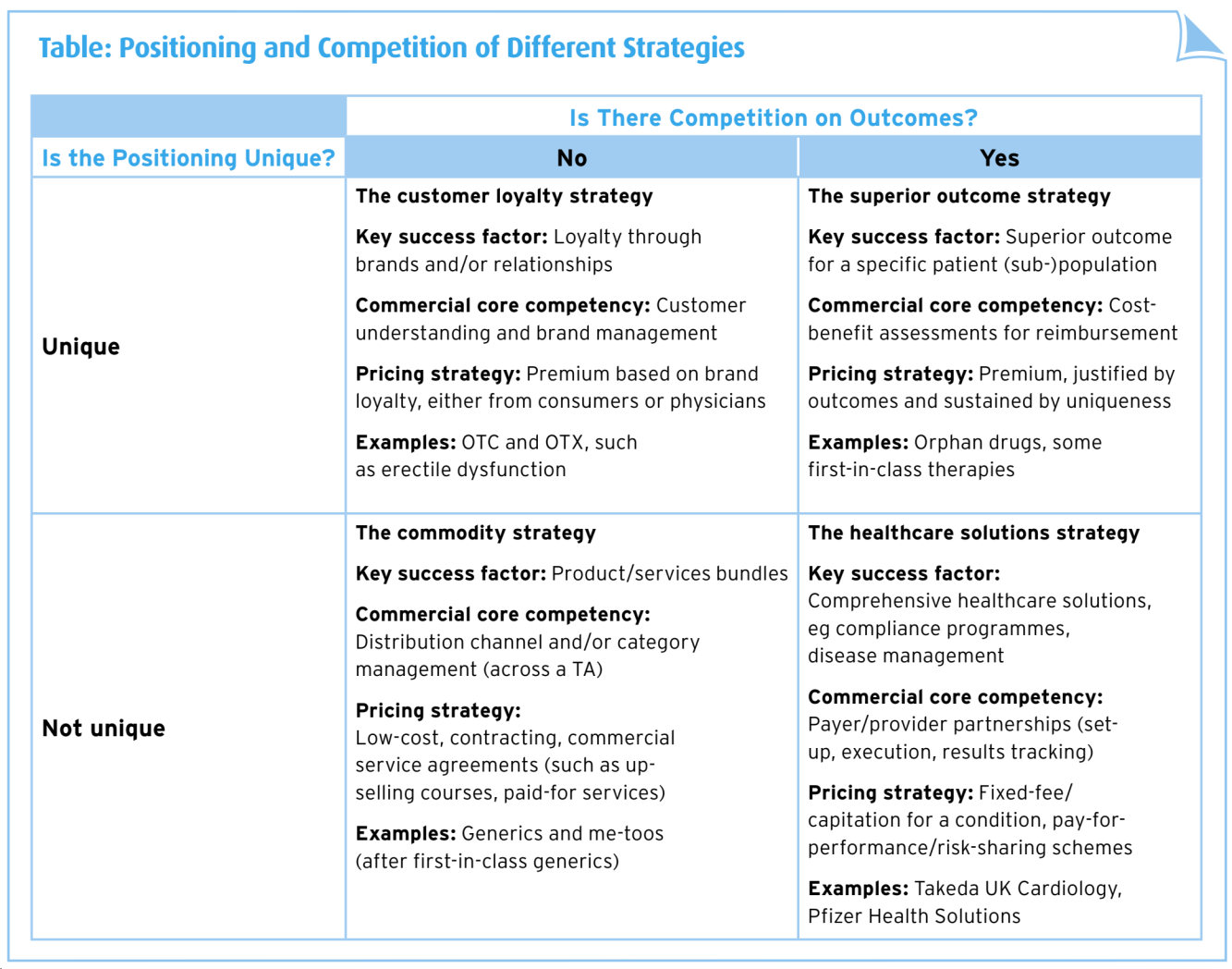

Two major dimensions drive the value of pharmaceutical offerings. The first relates to product uniqueness and this is the pharmaceutical marketer’s traditional ground. In the past, all patent-protected products were regarded as innovative (and therefore unique), including first-in-class active ingredients and me-too products. Now, payers reject this positioning, particularly in crowded therapeutic classes where generics exist.

The second dimension relates to the ability to compete on outcomes. Ideally, the clinical profile of unique products should translate into superior outcomes, but this is not a given. Good examples are drugs to treat rare diseases where no alternative exists. Yet even breakthrough medicines will have to stratify patients to compete on outcomes measured using cost-effectiveness analysis.

The message for marketers is clear: in the future, differentiation will be about more than an active ingredient with a good safety and efficacy profile. The four categories identified have unique key success factors, require tailored commercial core competencies and follow optimised pricing strategies.

More demanding and heterogeneous customers will require changes to the marketing organisation, beyond merely adding “market access” to the title of current product managers. The above strategic choices are not entirely exclusive and companies must work to demonstrate outcomes upstream during development and be ready to ‘fight it out’ later on. This does not mean adopting the current “risk-sharing” approach to achieving market access. It is our view that such schemes are a consequence of inadequate upstream preparation of the value story. If not resisted, these schemes will quickly become the norm, limiting both uniqueness and outcome differentiation.

Avoiding the commodity strategy requires significant investment, made early and sustained over time. These investment decisions cannot be made by global marketing in isolation, as the market conditions and payer needs will be crucial inputs to the creation of a superior outcome strategy. Increasingly, companies investigate payer needs during phase II of the development programme. We predict that this analysis will move completely to the start of the development process, modifying the “what is the unmet need?” question to a more nuanced “what is the improved outcome that payers seek and how much are they willing to pay for it?”